Disclaimer: This post talks openly about sexual assault.

A little over a year ago, I was sexually assaulted in the back of a taxi by a man I had met an hour earlier.

My housemate and I were drinking in a bar on Clapham High Street in south London when we met a group of men and women inside. They told us that they were having a house party and we should come. The bar was beginning to close, and I was filled with that familiar drunken urge to continue my night somewhere, anywhere—so, we did.

My housemate and I piled into a taxi with our newfound group of friends. The radio was blasting chart music and the air smelled like stale cigarettes. In the backseat, I sat next to a man I’d spoken to briefly on the dancefloor earlier that night. He’d approached me while dancing and I’d told him I had a boyfriend. At the time, that was true. I thought little of the encounter. As we sped towards the party in the taxi, with my housemate chatting away to the taxi driver in the front seat, the man from the dancefloor reached over and assaulted me. I felt my breath catch in my throat, and although I found myself wanting to scream, I said nothing. Instead, I looked out the taxi window at the blur of passing streetlights and waited for it to be over. It lasted less than a minute, but I would think about it for months afterwards.

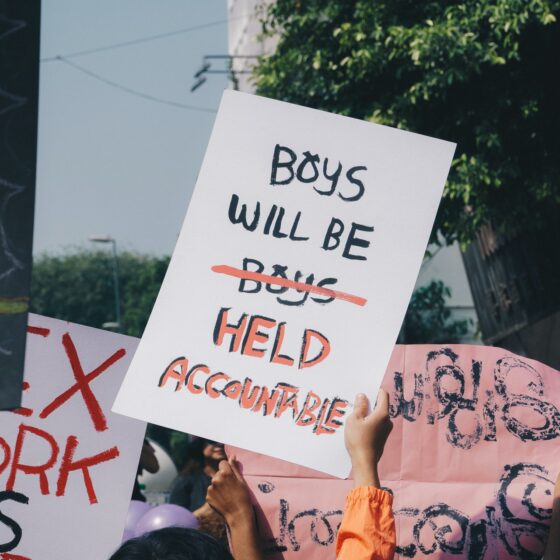

As women, we’re taught from a young age to comply with a list of non-negotiable behaviors to ensure our own safety

For a while, I felt as though I couldn’t properly articulate what happened to me, because I had done too many things ‘wrong’. When it happened, I hadn’t screamed or thrashed out when he assaulted me, but instead froze and remained silent. Wrong. Even when we arrived at the party, I didn’t cause a scene. I quietly told my friend that I wanted to leave, and I even said goodbye to him. Wrong. I had been drinking, which, fortunately, gave me a kind of numbness. Wrong. He had been a stranger, and I still got into a taxi with him. Wrong.

As women, we’re taught from a young age to comply with a list of non-negotiable behaviors to ensure our own safety. These range from the obvious (no headphones when walking home alone at night) to the more complex and harder to negotiate (have fun and drink, but don’t get too drunk, and remember that it’s fine to show some skin, but not too much). Since my teenage years, I learned how to police my own body and actions, as though acting in a certain way would prevent the inevitable. I tried and failed to find that desperate equilibrium between carefree and cautious, but in search of the balance, I didn’t stick to any of the rules I had learned. Last year, I was drunk and sloppy. I was careless, and my wrongs had stacked against me. What could I have possibly expected? And, so, for a while, it felt like the shame and terror that I felt inside was on me and me alone.

In my mind, he got off free.

When I relayed the story of what happened to me to a select group of friends, I was met with equal parts concern and fury. At the time, I couldn’t properly explain how it made me feel, and so I said little, telling them the bare bones of what had transpired before shutting it away in a corner of my mind. In reality, the experience had made me feel a deep shame, as though I wanted to sit in a shallow bath for hours and scrub at my skin. I felt tainted. Unclean. Changed by someone else’s doing, as though I was no longer the same person I was before.

For weeks after, I would try—and fail—to not think about what happened. For a while, every man in a black beanie was my assaulter. I saw him on the street, shouting into his mobile. He was there in the pub, nursing a pint. He was in stores, or parks, or taking up residency in my mind rent-free. He was everywhere. Whenever I’d see a man who resembled him, my mind would begin to race, and my breathing would become quick and labored. For a while, nowhere felt safe. What was even worse than being plagued by the ghost of the man who assaulted me, was that I knew, for him, I was nowhere in sight. He probably hadn’t given me a second thought. Yet that one moment in the back of a taxi played on loop in my mind.

My anxiety and trauma began to impact me at work. One morning while working, I had a panic attack. At the time, it felt out of the blue, but looking back, it seems impossible that it wasn’t a direct reaction to my assault, which had happened one week prior.

I’ve never spoken openly about what happened to me last year until now. By speaking this into existence, I want to legitimize my own experience of sexual violence. For a while, I felt ashamed, as though what had happened was my fault. I hadn’t complied with the obligatory list of behaviors that would ensure my safety, and I paid the price.

I’m choosing to speak honestly about what happened to me, because for many young women my age, this kind of story is all too familiar. We downplay our experiences of sexual violence and we end up blaming ourselves. As women, we know that, inevitably, any report of assault will result in our every move being scrutinized. What were we wearing? Were we drinking? Who were we with?

We’ve seen victims ripped apart in brutal cross examinations, where every detail, down to the underwear they wore when attacked, is used to undermine their credibility. We know that despite around 85,000 women being raped in the UK each year, only 1 in 25 reported rapes will end up in court, and an even smaller amount will end up in a conviction. The systems that are supposed to protect us fail us.

I’m shifting the blame. I’m not responsible for my assault, and you’re not responsible for yours

So, we blame ourselves. We compartmentalize our own actions into what we did ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, because this is what we’ve been taught to do. In doing so, we delegitimize our own trauma. We use passive language which centers the victim and completely erases the identity of the assaulter. We talk about ‘violence against women’ and ‘women’s safety’, placing the actions of assaulters and rapists onto the backs of women to figure out and process on their own. Yet, in all of this, it seems as though society has set the bar so low for men, that the onus is placed squarely on women to ensure their own safety. Men have been removed from the conversation without us even realizing it. It’s time to reclaim a narrative that often blames victims. It’s the first, small step in taking back control.

So, I’m shifting the blame. I’m not responsible for my assault, and you’re not responsible for yours. I no longer feel ashamed for what happened to me or shame for believing it was my fault. It wasn’t. And it wasn’t your fault either.