“What were you wearing?”

“How much did you have to drink?”

“Why did you go to his house?”

“Are you sure it wasn’t all just a misunderstanding?”

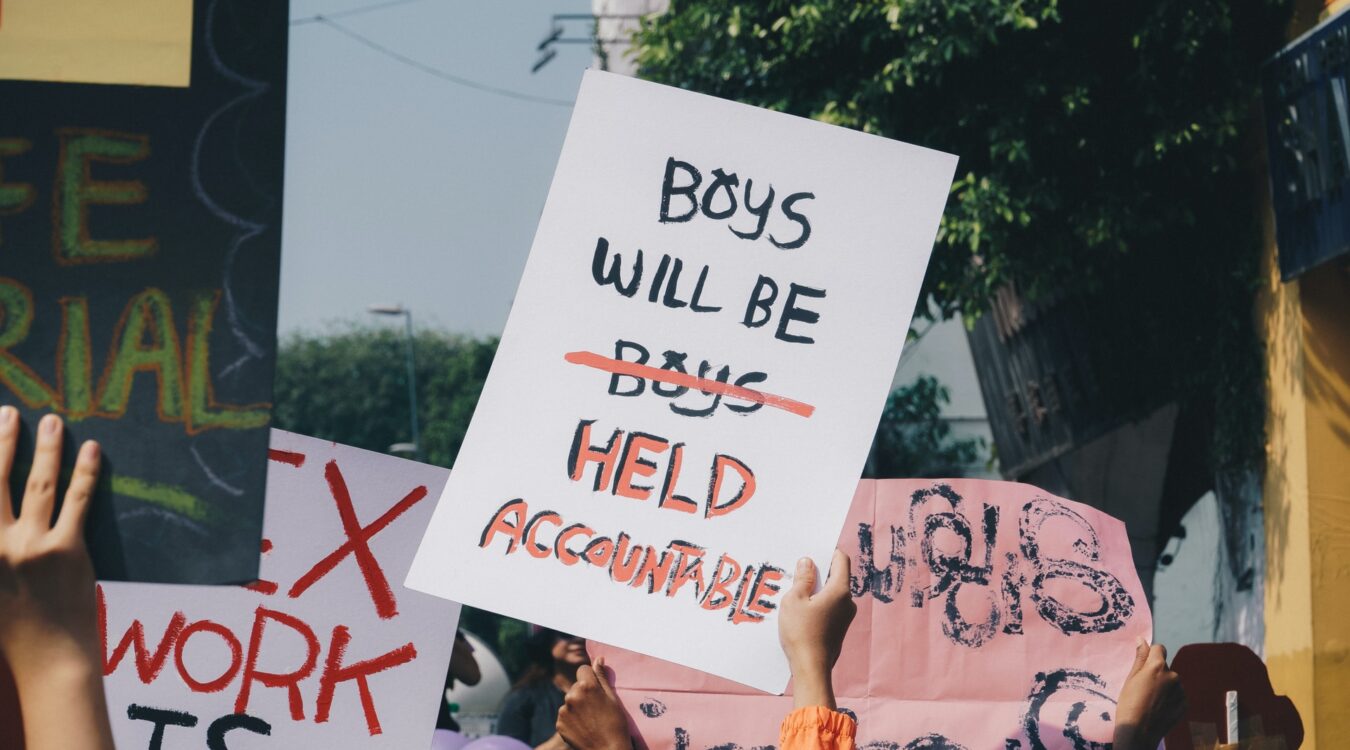

These are just a few examples of the questions that survivors of sexual violence commonly have to field. These questions might come from police officers or lawyers, from friends or family members or partners, or—if they speak out about their experiences publicly—from complete strangers. The clothing question is so common that Oregon State University created a moving exhibition titled What Were You Wearing?, using clothes as a way to showcase survivor stories.

The exact framing of these questions might be slightly different each time, but the message is the same. When people ask them, they are implicitly or explicitly asking the survivor how can we make what happened your fault?

These questions are often prefaced with a disclaimer like, “I’m not victim blaming, but…” But if you ask these things, or tell a survivor that they could have prevented their own assault by changing their behavior, victim-blaming is exactly what you are doing.

When we victim-blame, we make the world less safe for all survivors

As a current doctoral student studying #MeToo literature, I have noticed in my study that victim-blaming or shaming has appeared in virtually every single work I’ve read, fiction and non-fiction alike. Even more striking is the way in which the same themes emerge again and again: clothing, alcohol consumption, sexual history, not fighting back, not saying no unambiguously enough, not leaving a place or relationship soon enough, walking home alone, being in the wrong place at the wrong time. You name it. If it can be utilized against a woman to diminish her assault and put the onus on her, it’s used.

So what can we do for survivors of sexual assault?

Well, we need to implement new changes in structure.

Unfortunately, none of these victim-blaming and shaming problems can be fixed overnight. Large, structural changes are needed, and those things take time. Here are a few of the things that will need to happen if we want to create a world in which sexual violence is rare and survivors are supported:

Revamp Sex Education

Many young people are still receiving sex and relationships education that gives little to no airtime to the nuances of consent. Even at 31 years old, I still have vivid memories of the sex-ed class I, along with the other 13 year olds in my class, attended. We were herded into a room and told—in lurid detail—about the horrors that could happen to us if we wore short skirts, drank too much alcohol, or walked home alone at night. But was the topic of consent ever mentioned? No.

Proper education about consent for young people of all genders is ultimately the key to solving the sexual violence epidemic. Only by removing the mystery and shame from sexuality will we create a world where yes means yes and no means no. And from that place, we can empower people to make the decisions that are right for them without harming anyone else.

Proper education about consent for young people of all genders is ultimately the key to solving the sexual violence epidemic. Only by removing the mystery and shame from sexuality will we create a world where yes means yes and no means no

Change in Our Legal System

Chanel Miller, the author of Know My Name and the survivor in the infamous Brock Turner Stanford rape case, describes having everything from her clothing choices to her sexual history called into question by Turner’s attorney and supporters.

Change in the way the legal system handles sexual violence is desperately needed. The current process is so retraumatizing, and often so focused on finding a way to blame the victim, that many survivors choose not to report, not to press charges, or to drop their cases. According to RAINN, out of every 1000 sexual assaults in the U.S., 975 perpetrators will walk free.

Though “innocent until proven guilty” is a vital bedrock of our legal system, it does not need to go hand-in-hand with “survivors are crazy, vindictive, or liars unless proven otherwise.”

Aside from structural changes, there are also actions we can take right now to support the survivors in our families, friendship groups, and communities. (And if you think you don’t know any survivors, statistically, I promise you are wrong.)

Rethinking What We Say

When an allegation involves a high-profile person or is the subject of media coverage, we only have to look at comments sections or social media to see the ways in which survivors are undermined. When survivors share their stories publicly, they are often told that they were “asking for” what happened to them, or given unsolicited advice on how to avoid getting assaulted in the future.

Even if you would never dream of telling someone they were “asking for it,” you might be perpetuating victim-blaming in more subtle ways. Though it’s most visible online, victim-blaming can and does happen in all kinds of settings. Friends, communities, and even families will often go to surprising lengths to protect one of their own who has committed assault.

If you hear victim-blaming rhetoric from a friend or family member (ex. rape jokes, dismissing a survivor’s story, etc.), call it out if it’s safe for you to do so. Most importantly, listen and believe survivors when they share their stories.

What Not to Say

If someone discloses that they’ve been assaulted, you might not know what to say. It’s easy, in those moments to say something that comes across as insensitive or as blaming, even if your intentions are good.

Don’t pry for more details than they want to share, don’t question the survivor’s actions, and don’t push them to take a specific course of action (such as reporting). Though it might seem supportive on the surface, don’t introduce violent rhetoric (“I’m going to kill him/punch him/beat him up.”) The last thing most survivors want is more violence.

What to Say

Start with the words “I believe you. I’m so sorry that happened. How can I support you?” Then listen to the answer and hold a space for all the complicated, conflicting, and painful emotions they might be feeling.

In a world that so often blames the victim, simply being believed can be the first step on a survivor’s journey to healing. I invite you to be that person for somebody.

Be Part of the Fight For a Safer Future

Victim-blaming isn’t just hurtful, it is damaging on a profound level. A 2006 study by Professor Courtney Ahrens at California State University found that survivors who don’t feel supported when they speak out are less likely to disclose again in future. Some participants were left feeling that they would not get access to support if they told anyone about what had happened to them, and so staying silent became a form of self-protection. One participant received such an unsupportive response from a family member that she did not tell anyone about her experience again for another nineteen years.

When we victim-blame, we make the world less safe for all survivors. We create a system of so-called personal responsibility where the message is not don’t violate people but don’t get violated. We push sexual violence back into the shadows and create a culture of silence that allows abuse and abusers to thrive.

None of us can bring about these changes alone. We can and should keep speaking up, keep campaigning, and keep pushing for change. Progress has been made, but, still, there is a long way to go.